Previous Chapter

Previous Chapter Previous Chapter Previous Chapter |

Table of Contents | Next Chapter |

| Natural Borders Homepage |

This chapter serves to summarize the more detailed descriptions of the nine Community Resource Units (CRUs) provided in subsequent chapters. The chapter is divided into the following sections:

A. A Summary of Cultural Descriptors

B. Key Findings Related to Community Life

C. Key Findings Related to Public Lands

D. A Summary of Citizen Issues Related to Public Lands

Tables One and Two at the end of this chapter draw upon census data referred to in the following pages.

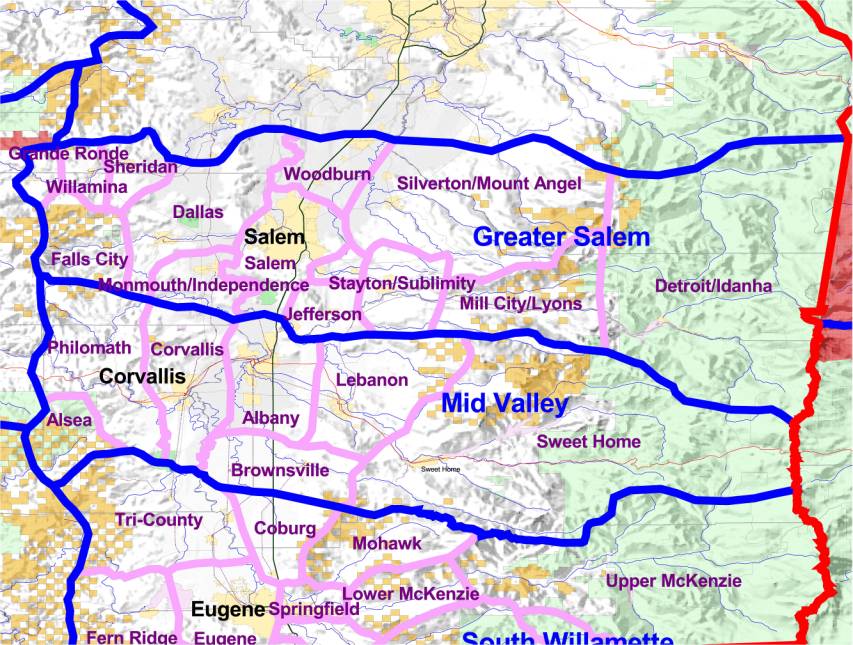

The Greater Salem Human Resource Unit (HRU), presented in Figure Six, includes all of Polk and Marion counties, plus the southern portion of Clackamas County. A small part of southern Yamhill County also falls within the Greater Salem HRU. A more precise HRU definition based on census block group identifiers, is found within the 1990-2000bg.xls data file on the distribution CD. Twenty-five incorporated areas are included within this HRU, with the largest being Salem (136,924) followed by Keizer (32,203) and Woodburn (20,100).

Marion and Polk Counties are often considered one unit. The Salem Area Visitors' Guide, for example, lists attractions in both counties. There is broad recognition that this area functions as a single social and economic unit, and several organizations use the term, "Marion-Polk," such as Marion Polk Legal Aid Service, Schools Credit Union, Real Estate Services, Inc., Healthy Start, Gleaners, Inc. Food Share, Medical Society and others.

Figure Six

Map of the Greater Salem Human Resource Unit (HRU)

Forest Service lands make up much of the higher elevations of the Cascade Mountains, and BLM lands are located in the mid-level elevations on both the east and west side of the unit, while most of the land base is comprised of the flatlands of the broad Willamette Valley.

The area within the Greater Salem HRU was among the first in Oregon to be settled by Europeans in the late 1840s. The Applegate brothers settled in the Dallas area and created the Applegate Trail on the west side of the Willamette River Valley and beyond to foster greater pioneer inmigration. People streamed into all areas of the HRU during the next few decades, establishing most of the communities now extant.

According to the 2000 census, the Greater Salem HRU has a total resident population of 360,790 persons, an increase of 23.8% over 1990 levels.

Population growth over the last decade in the HRU showed a distinct pattern. While the urban zone of Salem showed a substantial growth rate of 18%, the nearby smaller towns showed significantly higher growth, while the very rural, most outlying towns showed population loss. Thus, Dallas (21%), Gervais (47%), Independence (26%), Jefferson (23%), Keizer (29%), Monmouth (19%), Silverton (21%), Stayton (25%), Sublimity (29%), and Woodburn (30%) grew significantly, as indicated, while Detroit (-1%), Gates (0), Idanha (-3%), Lyons (6%), Mill City (0), Mt. Angel (9%), and Willamina (3%) only grew a small amount, stayed the same, or even lost population. Table Two at the end of this chapter may be examined for further review.

"It's been exploding with growth, if you look at building records last year. The housing here is 25% less expensive." [Woodburn]

Hence, settlement has followed a pattern of concentration in the "flatland" communities between the mountains and the Salem urban center. Other sections of this chapter will describe the social and economic consequences of this settlement.

Children ages 5 to 17 within the HRU increased by 27%, while those 65 and over fell from 14.3% of the population in 1990 to 12.7% in 2000. The dependency ratio, which measures the balance of children and retirees over those 18 to 65, fell 5.5%, indicating that the high growth in the childhood population is balanced by comparable growth in the labor force.

A similar distinction to the population comparison can be made related to the proportion of the population under 18. The same communities that gained significant population also gained a significant portion of children and young families. Those communities experiencing population stability or loss also lost a high proportion of children and young families.

The racial composition of the HRU changed significantly, as the area added 33,493 Hispanics and 2,249 Asians over the decade. The non-White population increased from 7.9% to 16.6% over the ten year period. The racial migration is an important feature of social life in virtually every community of the HRU. Woodburn experienced the most Hispanic growth and Hispanics now comprise 50% of the population, up from 29% in 1990. Woodburn is now the largest city in Oregon with over 50% of the population being Hispanic.

Residents in every community had stories about the emerging presence of Hispanics in their communities.

"I like the fact that there are now Mexicans and a couple of black families. If you have all the same type of person, things get boring. I think it has been good for the town." [Gates]

"There are continual changes with Latinos here. I have a neighbor who would always speak poorly about Hispanics. I arranged for her to volunteer at an after-school mentor program where she teaches knitting. The class filled with Hispanic women and now I see how my neighbor's attitude has changed. The schools are not as sensitive as they should be either. Now there is a family history day and cultural awareness fair that happens every year in Mill City." [Mill City]

"I used to take my kids out to pick strawberries. It was a tradition in the community. Now, with Hispanic fieldworkers, there aren't opportunities for children to pick strawberries for harvest." [Stayton/Sublimity]

Household composition also experienced a shift over the 1990 to 2000 period, with 3,539 more female headed households (a 47% increase) than in 1990. By comparison, married couple households increased by 16% from 60,207 to 70,050. The size of area households and families remained about the same, with little change in the proportion of single person households. The proportion of households living in their owned home remained about the same as at the start of the decade - 60%.

Migration patterns have changed somewhat between the 1985-1990 and 1995-2000 periods tracked by the census bureau. For example, 30,532 persons moved to the HRU area between 1995 and 2000, compared to 31,879 between 1985-1990. This shows a slowing in the migration from other states. A similar decline or slowing in migrants from other parts of the State of Oregon is also noted. On the other hand, the number of HRU residents who moved to a new residence within the HRU increased by 34% from 70,576 to 94,636, reflecting heightened internal migration within the area. "Moving up" through the purchase of newer or larger homes appears to be a trademark of the kind of migration experienced by the HRU over the previous decade. It also relates to the shifting labor market triggered by the decline of timber production, as workers deepened a pattern of commuting to urban areas for work.

Income grew throughout the area by 52% over the decade. Public assistance fell by nearly 17%, however, as the welfare reforms of the mid 1990s began to take effect.

Homeowners paying mortgages in excess of 30% of their income rose by 7,706 households from 14.1% to 23% of all homeowners. Renters paying in excess of 30% of their income in rent rose by 703 renters from 2.3% to 4% of all renters.

While the overall poverty rate remained almost unchanged for the decade, there were significant racial differences in these patterns. While Hispanics in poverty increased by 130% from 6,156 to 14,197, the numbers of Asians and American Indians in poverty actually declined by 33% and 23%, respectively.

The HRU's economy is supported by a healthy mix of industries. Important transitions are underway, however. Industries with declining percentages of the total from 1990 to 2000 include Agriculture (from 6.4% to 4.7%), retail trade (from 16.7% to 11.2%), and Manufacturing (from 14.4% to 12.8). During the same time period the area experienced a growth in a broad range of service industries - business services (increased from 3.9% to 6.9%), entertainment and recreation services (from 1.1% to 1.9%), and health services (8.9% to 11.5%) all displayed rapid growth and expansion.

The occupational distribution of the area follows the shifts occurring in the industry sectors. For example, while employees in the crafts and precision trades increased in number, their proportion of the total labor force declined from 10.2% to 9.5% over the decade. Managerial, professional and executive occupations increased significantly in both number and proportion, adding more than 15,000 new positions over the decade. A similar expansion is seen in the related technical, sales, and administrative support occupations.

The major economic activities in Polk County relate to agriculture, forest products, heavy manufacturing and education. The major agricultural products are grass and legume seeds, specialty and dairy products. Major employers of Marion County include NorPac Foods in Stayton, 600 workers, Freres Lumber in Lyons, 200 workers, and Green Veneer, 90 workers (Community Profile, Oregon Economic and Community Development Department, 2002).

Transition from a timber economy is still very much in evidence. Among rural people there is still a profound feeling that the changes have not made sense, reflected in themes such as the following,

"People don't matter now as much as birds and critters."

"Even dead trees are not harvested."

The urban zones have absorbed a large proportion of rural workers, according to many residents in all the small communities surrounding Salem.

The most widespread theme of what citizens reported is, "We have become a commuting economy." While this appears to be an obvious observation, the frequency of its statement and the nuanced descriptions provided by residents emphasized the profound meaning this change has effected. The positive aspect is that workers have been able to adjust to a post-timber world. Many people said, "We used to travel up the mountains for work [in the mills] but now we travel down to the cities for work." In many cases, we were told this change has been positive for quality of life and for standard of living. Once past the political rhetoric about whether or not reduced timber production has been appropriate, people indicated that their income often went up and that their life options had expanded. Particularly, the educational and career choices available to young people had expanded, residents reported.

The post-timber commuting economy has had a number of negative consequences as well. People are busier. The commuting time takes a toll on leisure time and family life. Significantly, the smaller communities reported a loss of leadership because of the commuting economy. Professional people especially are now commuting to the cities and are less involved in community life and leadership functions in their communities. The after-school hours for children have become a social problem in their own right, with "latch key" children involved in neglect or juvenile crime, and many schools and communities beginning after school programs.

Finally, the commuting economy has had an enormous negative impact on the economies of small rural communities. Rather than a "family wage job" at a mill, workers have 2 to 3 lesser paying jobs in recreation and support services. Rather than the seasonality of the timber sector, they deal with the more severe seasonality of the tourism sector. The loss of a timber base has shrunk the number and output of local commercial and retail enterprises, and the loss has been accentuated by the rise of "box stores" - the large commercial stores in the more urban communities. As a result, the small rural towns have experienced tremendous "economic leakage" whereby local residents spend a large and increasingly large proportion of their salary outside their communities. With the establishment of commuting patterns, it has become easy and common to shop for the family as part of the work routines, thereby further debilitating the ability of the small communities to sustain their local businesses.

"I'm beginning to sell out my land because I can't afford to farm anymore." [Dallas]

2. Rapid growth in the flatland communities between urban and rural areas:

"We moved here six months ago from Corvallis so that my husband and I could be closer to our grandchildren. It's a very welcoming town. I have already made friends." [Dallas]

"We moved here because land was cheaper than in Salem, and we like the area. It took me two years to get a local job that would support my family." [Mill City]

"People from the city move to the country to enjoy the wildlife, but they bring their dogs and then wonder why there's no wildlife." [Monmouth]

"People come here for the 1950s image, an idealistic vision of small town life." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"We moved here after we retired and visited my brother here." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

3. A growing Hispanic presence that is felt most in the schools and new business, but not yet expressed politically in terms of elected office.

"Hispanics used to come here on a seasonal basis to work on crops, but farms now use mechanized labor. There isn't the demand for crop pickers. They are staying because there are services like health care and barrios became established to absorb families into the community." [Stayton/Sublimity]

4. A sustained agricultural sector that is valued culturally and economically.

"In the summer, you have to be careful of the combines on the road [related to seed operations]. Also, it's the Christmas tree capital here. In November, there are lots of trucks here." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"It's hard to agriculture here today. You still see migrants during the 'seasons.' There is a migrant camp near us." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

5. Vulnerable small town economies.

"It's hard to own a small business in a small town." [Dallas]

"Ten years ago, there used to be four beauty shops, now there's one. There used to be a bunch of grocery stores, now there is one. There used to be a True Value but it's gone. Six restaurants, now there are three. Two meat stores, now none. No auto parts stores." [Mill City, Lyons]

"The lack of a grocery store, pharmacy and neighborhood shopping centers makes it hard to attract newcomers." [Monmouth/Independence]

"Many local stores went under. There was a Dime Shop where Factory-2-U is today, the fabric shop, the music shop, and the performing arts center. There was an antique business but now there is E-Bay." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"In the late 1980s, mom and pop stores were thriving. J.C. Penney's was the core of the downtown. The phone company had more than 100 workers. Now, ten years later, Penney's and most of the family-owned shops have shut down, and those 100 employees have evaporated into air." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

"Locals choose to patronize stores in Salem instead of locally owned businesses. Downtown used to be a thriving shopping district before it committed suicide." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

6. From going "up the valley" to mill work to going "down the valley" to city work. The economic integration of small towns and the urban center has been one of the key features of social life in the last generation. Whereas in the prior generation, small town economies were relatively intact, as evidenced by local mills and an active small town business climate, today in the commuting economy, it's all become blended together.

"Kellman's went out of business two years ago. The owner still lives in town but can no longer afford to keep the store open. He just couldn't compete with the superstores in Salem. But the store had strong ties to the community. The storeowner would have charge accounts for people unable to buy groceries when the timber industry began to decline." [Mill City]

"In twenty years, this area will be totally part of the Salem economy, like Gresham is to Portland." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"Since Highway 22 became a four lane, I can get to downtown Salem faster than my brother who lives in South Salem." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"Over half the teachers live in Salem." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"I'm going to nursing school in Portland. I come home the weekends to visit my parents." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

7. Economic transition. The commuting economy is regional in scale so that trades and services are offered on a wider basis than previously. New economic sectors, such as the growth of retirement and high tech manufacturing, are evident.

"I moved here from the east coast to care for mother-in-law. She is ill and very elderly. She is from Seattle and came here because of the high quality elder care available." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"People here do trade work, you know, shutters, gutters, dry wall, those kind of things. Some of this they do here, but they also drive to other areas." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

8. Vibrant, resilient caretaking systems in the small towns, as evidenced by the food banks, church support groups, and individual network caretaking reported by residents. Despite, or perhaps because of, the rapid changes of the last decade, residents in the small towns reported well-functioning caretaking systems at the informal level.

"The other night, I had to get my father to the hospital, but I couldn't open my front door because of the snow. The ambulance couldn't get near the house. I used the phone tree and within minutes, friends were digging me out." [Detroit]

9. Social and economic changes are associated by residents with increased criminal activity in the rural areas.

"There is a serious criminal element here. Neighborhood Watch is a good answer but they are walking a tightrope. They're almost too nosy." [Falls City]

"Vandalism and petty theft are increasing. The Senior Center has been broken into twice in the last year." [Mill City]

"Section 8 housing has been bad for the community because the tenants are not local but delinquents from Salem and the surrounding area. It has changed the dynamics of town." [Mill City]

"There is a marijuana growing problem here. It's not just one kind of person. It can be kids or older pros. There's an eleven year old 'pusher' in the elementary school." [Mill City]

Personnel from the Salem Field Office of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) stated that their mission was broadened in the 1990s from timber production to a more holistic approach emphasizing forest management, wildlife, and hydrology. A staff person shared many of the management concerns of the office related to the growing urbanization of the Willamette Valley. Among them are these:

1. The growth of the urban interface. More homes are built in dispersed fashion next to public lands. Many of these people began to complain of management activities near their homes and have exerted a "not in my back yard" pressure on the agency;

2. The increasing interface has meant that the rules of engaging fire are changing. Now firefighters get more training in dealing with toxic fumes that burning homes discharge, and so on;

3. Urban impacts include gang activity from Portland, the creation of toxic methamphetamine labs on public lands, coupled with only two law enforcement people covering 400,000 acres;

4. Abuse by off-highway vehicles is increasing;

5. Toxic waste dumping and general garbage dumping is increasing;

6. Road degradation over time due to limited budgets to maintain them. Locked gates as a solution to dumping and road decline has not been popular with the public.

Within Salem proper, research showed that residents did not have an active orientation to public lands. Individuals were found who fished or boated on public lands, and RVs and boats were observed more in some neighborhoods than in others. However, as a society, the Salem area did not exhibit strong links to public lands. The primary reasons reported by residents are the distance to public lands from the city and the costs associated with travel to public lands.

However, outside the urban zone, residents did reveal a pattern in the use of public lands. Interestingly, Interstate 5 is not an important marker in terms of social divisions or recreation patterns, but the Willamette River is still used as a boundary. The river was important in determining early settlement patterns and continues to demarcate social divisions at the regional level. For recreation, residents west of the Willamette River related more to the coast and less to the Cascades, while for residents east of the Willamette River the opposite was true.

Surprisingly, many residents west of the river stated that the Cascade areas west of the crest were not used as much as other spots. Detroit Lake and Mt. Jefferson Wilderness are highly valued, but residents also stated that they were just as likely to push on into the Bend area and beyond. The winter snow east of the Cascades is valued, as is northeast Oregon for its isolation and dispersed recreation opportunities.

It is evident from this research that longer-term Oregonians are grieving the loss of public lands from the isolated, casual uses of prior generations. In days gone by, use of the forest was part of everyday routine, often part of work activities. Now, with more people, and more urban people who do not have the day-to-day knowledge of the land, Oregonians see more rules, more density, and more conflicts related to public lands. That is one reason why Forest Recreation passes are so resisted, and when reservations are needed to enjoy a traditionally-used area, then the "older guard" feels supplanted by new times. Longer-term residents are also actively seeking public lands that are less used.

"Our old places are too crowded now."

"Geocaching" as an emerging sport is very fast growing, as reported in local newspaper accounts and by sporting goods clerks at local stores. For example, the clerk in Salem's G.I. Joes said that their favorite class was GPS (Geographic Positioning System) navigation. This trend may influence public land management in the future [www.geocaching.com].

1. The loss of the timber lifestyle and economy is not just an economic loss but a cultural one for which people continue to grieve.

"Today, no one knows each other. People don't live with the land anymore." [Falls City]

"No one is cutting anything. It's not like it's doing any good out there." [wood products business, Stayton ]

"I tended bar 20 years ago in Falls City. It was alive then. Now it's a bedroom for Dallas, Monmouth, and even Portland." [Falls City]

"About 15 years ago, there were 15-20 logging companies in the canyon. Now there are only two large ones and two small ones. Where there used to be a logging truck going past every three minutes where the Gleaners are now, now there are maybe 5-10 trucks a day. There used to be 7 timber mills, now there are three. This means no taxes for schools, no art, no music, no home economics." [Mill City]

2. A sustainable timber lifestyle and economy by long term and mid-term Oregonians is still valued.

"We used to be a logging town, but now we are looking for other ways we can use the forest to make a living." [Dallas]

"We saw the mills close down, one by one. Then the school began to cut down. The high school was the first school in Detroit that closed." [Detroit]

"The main industry changed from the mills to gathering secondary woods materials from the forest." [Mill City]

"I used to collect pinecones but it's too dangerous anymore. I've heard of violent acts toward people stepping on the turf of other collectors. Local women here used to make a livelihood - shitake mushrooms, bear hair, other things, but now ethnic people from out of town have taken over." [Mill City]

"I'd like to see the timber industry come back. We get visitors out here and they're surprised when they see trees. They think we cut them all down." [Stayton/Sublimity]

3. A transition is continuing from timber to trades and services economy based on recreation and retirement. Residents are active in voicing a value for diversification and recognize the danger of replacing timber exclusively with recreation. Detroit, for example, with the low water levels at Detroit Lake last year, has undergone significant planning to diversify its economic activity.

"We can't always depend on the Lake being full." [Detroit]

"People don't work in the woods anymore, but play in the woods. Now, people work in the cities." [Detroit]

4. The nature of recreation is changing, from rural, dispersed, inexpensive to urban, organized, and costly. A vast number of people commented on the way recreation happened in the "old days" in the rural areas. The old pattern was to go fishing or hiking, go to local dances or to the new theatres on Lancaster Drive in Salem. Today, the focus is on "entertainment" - kids drive to Salem to the theatre or dances, it costs more money, it's going out, and downhill, to the urban centers. On the other hand, urban uses of public lands seems to be on the increase, with greater numbers of people and more organized events.

"You gotta go to Salem." [for recreation, Stayton/Sublimity]

5. The Watershed Councils play an enormously useful role in bringing diverse elements of the community together, fostering education on ecosystem issues, and in creating on-the-ground restoration projects.

D. A Summary of Citizen Issues

Related to Public Lands

Gates

"One time I was up on private land and the gate was open. When I came back it was locked. I had to drive hours out of my way to get back home." [Detroit]

"I think they work with private owners to get permission. But they will still drive on land that doesn't have a gate." [Monmouth/Independence]

"A locked gate doesn't mean you can't use the land." [Falls City]

"It is a constant frustration to guess when gates are opened and closed. If you travel up to Boise Cascade land, you are always susceptible to being locked in." [Monmouth]

Fire

"With all the newcomers and visitors, we worry about fire protection. They don't really know about how to do fires. I'm surprised there weren't more fires last summer than there were." [Detroit]

Water and Riparian Treatment

"Some folks have been trying for some time to build a greenway around the Willamette River, west of Salem. More and more property owners are developing right to the river's edge, which is starting to cause mass erosion." [Monmouth/Independence]

"I don't know who's putting out the new riparian rules. Who do I talk with?" [Detroit]

"How good can Salem's water be with all the lawns and fertilizers? I live on the outskirts and have a personal well. All my friends bring out empty jugs to fill up." [Salem]

"We used to get in the truck and go into the forest for hunting and fishing on the backroads. Now the roads are so deteriorated we can't go." [Detroit]

"The Forest Service is not taking care of the roads, so they become passable. Now we can't access the places where we fish and swim, like High Lake Road. They are planning on the area to become like Bull Run Reservations. All the roads are gated and the area is closed off to residents." [Mill City]

"Access is more and more of a problem." [common, Monmouth/Independence]

"I don't like all the road closures on State and BLM lands." [Stayton/Sublimity]

"There's not enough dispersed campgrounds. The woods are too full of people who are improperly camping. They bring the threat of fire." [Detroit]

"People litter a lot. I carry trash bags with me all the time and bring back bags of trash when I go hunting." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

"A lot of the trails in this area were started by locals and we helped take care of them. Now we have to get a trail pass and pay money." [Mill City]

"Those mandatory Forest Passes are just not cool. Where is the money spent that is supposed to be put back into the land. People are hiking on trails that aren't in good shape. My friends think that Forest Pass money will never actually be used for that purpose." [Salem]

"Private forest lands now are taking a beating. They are being forested too much, too soon." [Detroit]

"Private landowners aren't replanting trees within the timeframe required by law." [Monmouth/Independence]

"There are ways to make management work better for us." [Falls City, special forest products]

"The BLM permits for mushrooms cover three square miles. That's not realistic - it's too small for a commercial picker." [Mill City]

"We can't get good maps and the trails are not well marked. I have been here for three years, and it is still confusing which trials go where. Tourists are not going to start down a path when they don't know where it's going." [Detroit]

"People ask all the time for information about Valley of the Giants." [Falls City]

"We don't have adequate information from the Forest Service about recreation opportunities." [Chamber of Commerce, Stayton/Sublimity]

Outdoor Education

"Trails are being abused - littering, four-wheeling. People who are not forest savvy." [Silverton/Mt. Angel]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Previous Chapter Previous Chapter |

Table of Contents | Next Chapter |

| Natural Borders Homepage |