| Table of Contents | Next Chapter | |

| Natural Borders Homepage |

A Human Geographic Issue Management System for

Natural Resource Managers in the

Willamette Valley, Oregon

Chapter

One

Project

Background Report

Background and

Objectives

Management of

federal forest lands of the Pacific Northwest has undergone significant change

in the last fifteen years. In the Willamette River Valley, timber production

from public lands is a fraction of what it once was, and recreational uses have

been growing steadily. The urban areas surrounding public lands are growing in

substantial ways, while the rural communities near them are continuing to

struggle economically with the shift away from timber toward a recreation

economy and an urban-oriented labor base. Meanwhile, management budgets are

shrinking and skilled personnel are being lost. Without a budget driven by

timber receipts, land management agencies have to "do more with less."

In this climate of

changing management conditions, the Willamette National Forest, in conjunction

with the Siuslaw National Forest and the Eugene and Salem District Offices of

the Bureau of Land Management, used the services of James Kent Associates (JKA)

to conduct social and economic research in the human communities associated

with the Forest. Forest management wanted direct information from these communities

about the social and economic trends observed by residents, the current

orientation of residents toward public land, specifically the issues they have

about natural resources and the opportunities they see for resolving them. In

addition, the Forest wanted advice about how to communicate effectively with a

broader range of publics so that it can foster greater dialogue and

collaboration between Forest staff and community residents.

The specific

objectives of the Willamette Human Geographic Mapping Project were to:

1.

Use the Discovery Process in the Greater Salem, Mid-Valley, and South

Willamette Human Resource Units (HRUs) to describe the publics, networks,

settlement patterns, work routines, supporting services, recreational

activities, and geographic boundaries. The products of Discovery are:

a.

A human

geographic map, at two scales of geography, which reflects the culture of the

local area and the identity residents have with their landscape.

b. Description of key informal networks and

network caretakers in each HRU;

c. The range (emerging, existing, disruptive)

of actionable citizen issues related to natural resource management and

biosocial ecosystem recovery;

d. Strategies in each HRU for

culturally-appropriate communication (who, when, where, how);

e. Current

and future social and economic trends affecting each HRU, with implications

derived for "desired future conditions" useful for land use planning efforts;

f. Opportunities identified by citizens to

resolve issues, to create productive harmony (as called for in NEPA) between

physical and social environments, and to develop citizen ownership in public

land management through community-based partnerships;

2.

Use social, economic, and cultural information obtained through the Discovery

Process to develop a Geographic Information System (GIS) data layer. This data

layer is expected to complement the traditional bio-physical data employed by

the BLM and the Forest Service in order to broaden the ability of the agencies

to deal with both bio-physical and social components of the ecosystem. Such a bio-social

approach to ecosystem management will be realized through the following

objectives:

a. GIS

development of human geographic maps for the three HRUs at two scales of

geography, the HRU and the Community Resource Unit (CRU);

b. Aggregation

of 1990 and 2000 Census data (as available) according to HRU boundaries in

order to identify social and economic trends at appropriate cultural scales;

c. Integration

of quantitative census data with qualitative social and economic data of the

Discovery Process in order to present a holistic picture of local communities

for attachment as a database to the map layer. This documentation will be

useful for NEPA, land use planning, and day-to-day management;

d. Identification

of communication strategies, attached to the map layer, that will show how,

with whom, when and where to communicate at the informal level of community.

e. Provision of a summary report that shows

the framework of a Human Geographic Issue Management System (HGIM)™ on the

basis of the community fieldwork (The Discovery Process) and the GIS social

layer. Such a framework is designed to identify citizen issues at the emerging

stage of development, to promote staff capacity to respond in timely and

appropriate ways, and to develop projects and policy capable of broad-based

public support.

Teammates

who participated in this fieldwork are:

Kevin

Preister, Ph.D., Social Ecology Associates, James Kent Associates

Luis

Ibanez, Licenciado, James Kent Associates

Megan Gordon,

M.A. Anthropology, Oregon State University

Toby Keys,

M.A. Anthropology, Oregon State University

Kirsten

Saylor, M.A. Anthropology, Oregon State University

Armando

Arias, Ph.D., Dean, Social and Behavioral Sciences Center, California State

University at Monterey Bay.

James Kent, J.D.,

President, James Kent Associates

Mapping

support was provided by Paul Zelus and Walt Bulawa at Map Associates LLP,

Pocatello, Idaho. Team resumes are included in Appendix D.

Figure One

Project Staff from left to right: Luis Ibanez, Kevin Preister, Toby Keys, Megan Gordon, Kirsten Saylor, and Armando Arias

Methodology Used

The Discovery

Process (tm) is a means to describe a community by "entering the routines" of that

community in order to see the world as residents see it. Team members attend soccer

games and school events, go to cafes, gas stations, laundromats, taverns and

other gathering places. They are invited into people's homes. Following the

adage, "People hate to be interviewed but love to talk," they get in situations

where people tell stories about their community. They observe and interact with

residents to determine their interests and concerns.

In practice, the

JKA team contacted and listened to as many people as we could, to hear their

stories of the land, their family history, changes they are seeing on the land

and in their community, their use of public lands and ideas for improving

management. We learned how public land management affects different kinds of

people and what they think could be done to minimize the negative effects and

enhance the positive ones. We always asked people who else we could talk with,

and those people whose names came up several times we made a special point of

contacting. In addition, we frequented the gathering places in the area - the

restaurants, the laundromats, churches, and stores, engaging residents in

conversation.

We made a point of

talking with a wide variety of people - long time residents and newcomers, young

and old, farmers, loggers, townspeople, environmentalists, commuters and

storeowners. We talked to several kinds of recreationists - hunters, fishers,

off-highway vehicle enthusiasts, campers, and hikers. Our contacts included

officials from the many local, state, and federal agencies engaged in natural

resource issues, staff from many social agencies, mayors, and city

councilmembers.

In the Discovery

Process, the team was particularly interested in the seven Cultural

Descriptors, used by JKA as a community assessment methodology. The method is

outlined in more detail in Appendix B. The Cultural Descriptors are as follows:

Geographic Boundaries: Any unique physical feature that defines

the extent of a population's routine activities. Physical features generally

separate the cultural identity and daily activity of a population from those

living in other geographic areas. Geographic boundaries include geologic,

biologic, and climatic features, distances, or any other characteristic that

distinguishes one area from another. Examples of geographic boundaries include

topographic features that isolate mountain valleys, distances that separate

rural towns, or river basins that shape an agricultural way of life. Geographic

boundaries may be relatively permanent or short-lived; over time, boundaries

may dissolve as new settlement patterns develop and physical access to an area

changes.

Settlement

Patterns: The

distribution of a population in a geographic area, including the historical

cycles of settlement. This descriptor identifies where a population resides and

the type of settlement categorized by its centralized/dispersed,

permanent/temporary, and year-round/seasonal characteristics. It also describes

the major historical growth/non-growth cycles and the reasons for each

successive wave of settlement.

Publics: Segments of the population or a group of

people having common characteristics, interests, or some recognized demographic

feature. Sample publics include agriculturalists, governmental bodies,

homemakers, industries, landowners, loggers, miners, minorities, newcomers,

preservationists, recreationalists, senior citizens, small businesses and

youth.

Networks: A

structured arrangement of individuals who support each other in predictable

ways because of their commitment to a common purpose, their shared activities,

or similar attitudes. There are two types of networks, those that are informal

arrangements of individuals who join together as a way to express their

interests, and those that are formal arrangements of individuals who belong to

an organization to represent their interests.

Networks functioning locally as well as those influencing management

from regional or national levels are included in this descriptor. Examples of citizen networks include

ranchers who assist each other in times of need, grassroots environmentalists

with a common cause, or families who recreate together. Examples of formal

organizations include a cattlemen's association, or a recreational club.

Work

Routines: The way in

which people earn a living, including where and how. The types of employment,

the skills needed, the wage levels, and the natural resources required in the

process are used to generate a profile of a population's work routines. The

opportunities for advancement, the business ownership pattern and the stability

of employment activities are also elements of this descriptor.

Supporting

Services: Any arrangement people use for taking care

of each other, including the institutions serving a community and the

caretaking activities of individuals. This descriptor emphasizes how supporting

services and activities are provided. Commercial businesses, religious institutions, social welfare agencies,

governmental organizations, and educational, medical and municipal facilities

are all examples of support services. Caretaking activities include the ways people manage on a day-to-day

basis using family, neighborhood, friendship or any other support system.

Recreational

Activities: The way in

which people use their leisure time. The recreational opportunities available,

seasonality of activities, technologies involved, and money and time required

are aspects of this descriptor. The frequency of local/non-local uses of

recreational resources, the preferences of local/non-local users, and the

location of the activities are also included. [1]

One product of

using the Cultural Descriptors is an understanding of human geographic

boundaries. People everywhere develop an attachment to a geographic place,

characterized by a set of natural boundaries created by physical, biological,

social, cultural and economic systems. This is called a Bio-Social Ecosystem. The term was created in 1991 by James Kent and Dan Baharav to integrate

social ecology and biology in addressing watershed issues with people being a

recognized part of the landscape. Unique beliefs, traditions, and stories tie people to a specific place,

to the land, and to social/kinship networks, the reflection and function of

which is called culture.

The first Human

Geographic Maps (HGMs) came into existence in the late 1970s and early 1980s as

part of JKA's work with the US Forest Service, Region 2, Forest Planning

process. The USFS was looking for new and creative ways to empower citizens as

part of the Forest Plans. The HGMs were

published as a part of the Forest Plan implementation.

Seven different

scales of cultural or human geography have been discovered. Operating at the proper scale brings optimum

efficiency and productivity to projects, programs, marketing, policy formation

and other actions by working within the appropriate social and cultural context.

1. Neighborhood Resource Unit (NRU)

2. Village Resource Unit (VRU)

3. Community Resource Unit (CRU)

4. Human Resource Unit (HRU)

5. Social Resource Unit (SRU)

6. Cultural Resource Unit (CuRU)

7. Global Resource Unit (GRU)

The HGMs represent

the culture of a geographic area, especially the informal systems through which

people adapt to changes in their environment, take care of each other, and

sustain their values and lifestyles. The HGMs represent the boundaries within

which people already mobilize to meet life's challenges. Hence, their

experiences are used through their participation as place-based knowledge to

create ownership in issue resolution, project planning and implementation,

public participation, and public policy development.

For this project,

three scales of human geography were used, the Social Resource Unit (SRU), the

Human Resource Unit (HRU), and the Community Resource Unit (CRU).

Social Resource Units (SRUs) are the aggregation of HRUs on the basis of

geographic features of the landscape, often a river basin, for example, and are

the basis of shared history, lifestyle, livelihood, and outlook. At this scale,

face-to-face knowledge is much reduced. Rather, social ties are created by

action around issues that transcend the smaller HRUs and by invoking common

values ("We love the high desert.").

SRUs are

characterized by a sense of belonging. These are rather large areas and one's

perception as to the Unit's boundary is that when you cross the SRU boundary

you are in an entirely different culture. There is a general feeling of

"oneness" as being a part of this regional Unit. There is a general understanding and agreement on beliefs, traditions, stories and the attributes of being a part of the Unit.

JKA was directed

to conduct research in the urban areas of Salem, Albany, Corvallis, Eugene, and

Springfield, and the surrounding rural areas as well, from the crest of the

Cascade Mountains to the crest of the coastal range. Prior research of JKA determined that these communities are

embedded in a large, region-wide cultural zone that we called the Willamette

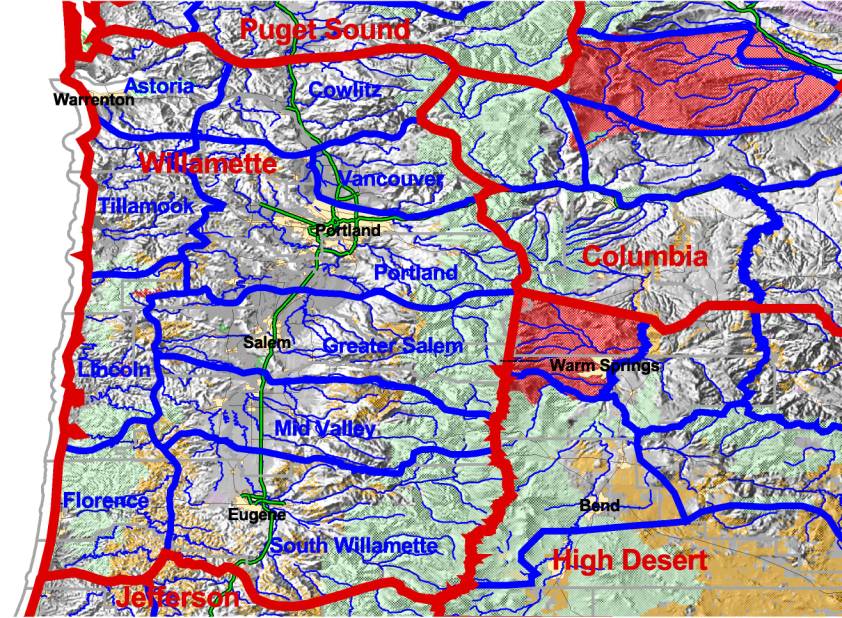

Social Resource Unit (SRU), as shown in Figure Two.

Human Resource Units (HRUs) are roughly equivalent in size to a county

but seldom correspond to county boundaries.

HRU boundaries are derived from the seven Cultural Descriptors outlined above.

HRUs are characterized by frequent and customary interaction. They reveal

face-to-face human society within which people

have personal knowledge of each other and well-developed caretaking systems

sustained through informal network relationships. People's daily activities

occur primarily within their HRU including work, school, shopping, social

activities and recreation. Health, education, welfare and other public service

activities are highly organized at this level with a town or community almost

always as its focal point.

Through this

research, we also determined that there were three Human Resource Units (HRUs)

that make up the targeted area, which we termed Greater Salem, Mid-Valley and

South Willamette HRUs, also shown in Figure Two.

Community

Resource Units (CRUs) show

the "catchment area" of a community, or its zone of influence, beyond which

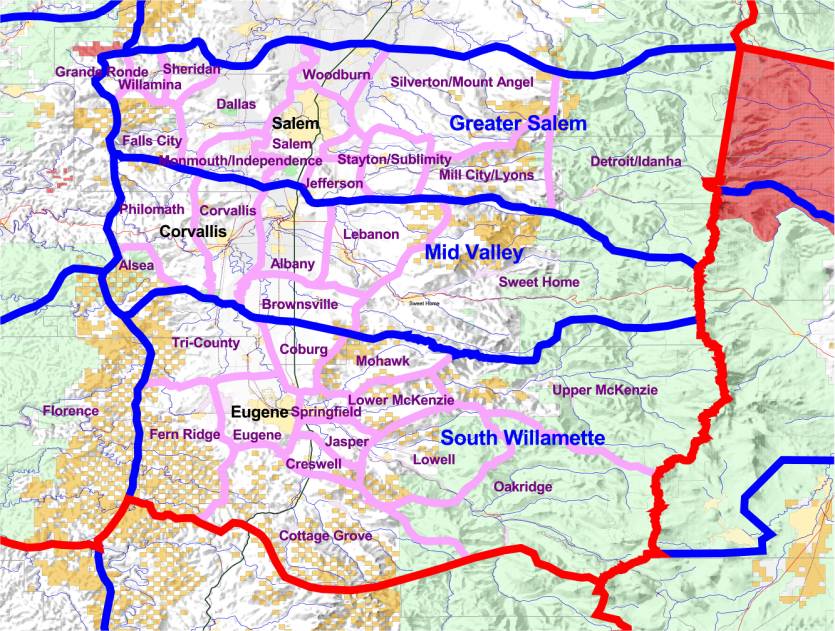

people relate to another community (Figure Three). Geographic features or

settlement patterns often determine these boundaries. At this scale, there is

great face-to-face knowledge, and the caretaking systems through informal

networks are the strongest. The three HRUs contain a total of 34 CRUs.

Twenty-three of them have chapters here, while limited resources prevented

description of the remaining eleven.

In addition to the

qualitative research methods embodied in the Discovery Process, 2000 census

data and available local information were used to augment the understanding of

local communities.

The research, and

the recommendations that accompany it, are structured in the GIS system of the

Forest into what JKA calls a Human Geographic Issue