Appendix A

Appendix A |

Table of Contents | Appendix C

|

| Natural Borders Homepage |

Appendix B

Methods for the

Development of

Human Geographic Boundaries

and Their Uses

By

Appendix A

Appendix A |

Table of Contents | Appendix C

|

| Natural Borders Homepage |

Appendix B

Methods for the

Development of

Human Geographic Boundaries

and Their Uses

By

James A. Kent J.D.

The James Kent Associates

P.O. Box 3165

Aspen, Colorado 81612

970.927.4424

jkent@jkagroup.com

Kevin Preister, Ph.D.

Social Ecology Associates

P.O. Box 3493

Ashland, Oregon 97520

541.488.6978

kevpreis@jeffnet.org

June, 1999

In 1998, the

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and James Kent Associates (JKA) signed a

cooperative Assistance Agreement for the purpose of furthering the emerging

paradigm within BLM of ecosystem management. As the term ecosystem management

has become interpreted broadly to include humans into the equation of public

land management, and as the collaborative partnership movement has broadened

and deepened throughout the country, additional resources for understanding and

incorporating community interests into decision-making have been sought.

Because of JKA's experience in the last thirty years related to these concerns,

its success in the field, and its well-developed methodology of community

assessment, mapping and management, JKA was asked to assist BLM in:

"refining and demonstrating community assessment methods to help the

BLM and its partners address social and cultural criteria for more effective

public participation and collaboration when making planning and other decisions

- a key element in building capacity for community-based approaches to land and

resource management."

JKA's

methods for performing community assessments through The Discovery Process (tm)

workshops, mapping human geographic units, and related management training can

help local governments, federal agencies, and community organizations better

understand and address social and cultural criteria. Also, JKA's methods add value to the human dimension of

bio-social ecosystem management, strengthening social justice considerations

while complementing more traditional, economics-based approaches. The BLM and

JKA share a common commitment to helping communities and federal land

management agencies work together in a more productive way.

This

paper focuses on the mapping component of a larger process termed the Human

Geographic Issue Management System (HGIMS). The system is designed to create

productive harmony between land and people through cultural alignment between

informal community systems and the formal institutions that serve them. The

system has two phases:

1.

The Discovery Process (tm) is the description of communities "from the inside out,"

that is, from the perspectives of people who live in those communities. By

focusing on Cultural Descriptors (publics, informal networks, settlement

patterns, work routines, support services, recreation routines and geographic

features, defined more fully below), a fairly complete picture emerges of

community life, communication patterns, important citizen issues, and social

and economic trends affecting an area. One product of the Discovery Process is

a human geographic map that shows, from a social and cultural perspective, where

one area ends and another begins.

2.

Issue Management (tm) is the process of identifying emerging issues in the

community and including them in the management process of planning and

implementing projects designed to maintain sustainability of people and the land.

It is a method of minimizing surprise and disruption by creating a predictable,

natural process of communication and action so that the well-being of both

community and the landscape is addressed.

The

balance of this paper will focus on the rationale for the creation of human

geographic maps. It will outline the methodology used for their development,

especially the seven cultural descriptors. It will close with our vision of how

a GIS-based HGIMS offers a powerful tool for responsive management in regional,

multi-jurisdictional, multi-species ecosystem projects.

Human

geographic maps were developed to provide a context for implementation of the

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It was discovered early that town boundaries, county boundaries and

regional planning boundaries did not provide the context needed for

understanding and implementing the social/cultural aspects of NEPA.

NEPA is well known as the first piece

of national legislation to declare a national policy on the environment. It has

attracted most attention for Section 102 that calls for the completion of

Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) for all "major federal actions." Most of

the political conflict and court cases have invoked the procedural adequacy of

the EIS. A report from the Council on Environmental Quality summarized

twenty-five years of experience with NEPA by saying procedural adherence to

Section 102 has led to a dynamic of "issue stacking" in which identified

concerns become included in the EIS process for analysis, accumulating

controversy as project review moves forward. The report, along with many NEPA

professionals, have recently begun to advocate for using the NEPA process not

only to identify issues early but to resolve them as the project is reviewed

(CEQ 1996).

Section 101 of NEPA, by contrast, has

been under-emphasized. It contains the clearest policy intent of the law. It

first acknowledges people's impact on the land through population growth,

high-density urbanization, industrial expansion, resource exploitation, and

technological advances. It then declares that it is the continuing policy of

the federal government, in cooperation with State and local governments, and

other concerned public and private organizations to

"...create and maintain conditions under which

man and nature can exist in productive

harmony, and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of

present and future generations of Americans" (emphasis added).

The

Bio-social Ecosystem Management Model (Figure 1) is a way to conceptualize the

productive harmony described in NEPA. Based on the long-standing observation

that the well-being of people and the land are inextricably tied together, the

figure makes the case that permanence and diversity are valued characteristics

for both physical and social environments (Preister and Kent 1997).

Sustainability is created when land use decisions are shaped around the

question, "How can we enhance the permanence and diversity of this physical

ecosystem in ways that promote the permanence and diversity of the human

communities?"

It is our view that the same level of

effort used to understand physical ecosystems must be applied to understanding

social ecosystems and to integrating the two in a holistic management system.

Moreover, in understanding

Figure One

(Source: Preister and Kent 1997)

social ecosystems, it is not enough to

understand the formal level of communities, i.e. the macro-level data, the

county commissions, and state government. Rather, it is important that research

methods reflect the social reality of everyday people--their routines,

traditions, beliefs and issues. We call

this the informal level of community. The Discovery Process (tm), the major

Our experience has shown that most

proposed projects that run into trouble, fall behind schedule, and generate

community opposition may technically comply with the legal and regulatory

requirements of their various local, state, and federal regulations. However, they often fail to discover the

real issues existing in the community that are held by people who don't come to

public meetings and are therefore excluded from the project design and review.

One of the major

Human

geographic mapping allows a resource manager to know where the culture borders

are in relation to management decisions. For instance, the Roaring Fork Valley

between Independence Pass and the confluence of the Roaring Fork and Colorado

Rivers (Aspen and Glenwood Springs) has three county governments and four town

governments with various jurisdictions associated with each government. If the resource manager recognizes the

Roaring Fork Valley as one social/cultural unit and manages within the informal

networks, the chances for program and project success increase dramatically.

The resource manager can then easily distinguish the difference between

place-based communities and regional or national publics of interest and

interact with them in a specific, appropriate manner.

In

the case of Environmental Justice Guidelines (EJG), necessitated by Executive

Order 12898 to which federal agencies must comply, human geographic mapping

provides the cultural boundaries so that the resource manager knows where the

resource management decision, or impact, ends culturally. Until human geographic mapping was created,

managers had no idea how far they had to reach to include the people affected

by EJG. Seldom, if ever, would it

include a complete county. However, it

could include two towns depending on the human geographic boundaries involved.

The

form of management required is clearly one of "participatory communication," in

which the proponent of the action engages the community within its cultural

boundary system in a manner consistent with its own cultural beliefs,

traditions, stories and approaches to the environment, including cultural

stewardship.

Human-geographic boundaries represent

the informal systems of communities. They reflect the boundaries within which

people conduct their lives. Day to day interactions, talks with neighbors and

co-workers, shopping, visiting and family ties operate within predictable

geographic patterns.

In our experience, human-geographic

maps represent a resource to land use managers and others involved in

experiments in ecosystem management and restoration. Based as they are on how

people actually live their lives, and how people mobilize their social and

physical resources to meet life's challenges, the maps provide an inside view

of the local terrain of a place-based culture.

Specifically, the advantages of

human-geographic mapping for bio-social ecosystem management are these:

Natural resource managers now have the capability to staff

the land base, with its attendant social and physical capital, as an integral

unit, rather than staffing programs structured with artificial administrative

boundaries. This capability of "staffing the culture" is a key strategy when

coordinating or integrating federal land management administration.

The maps reveal natural lines of mobilization and inclusion

of local residents, revealing limits of social ties;

Maps allow sensitivity in siting facilities and programs

that reflect how people actually identify with and use the land;

The mapping further promotes a bio-social model of

productive harmony, providing a rationale for including issues of community

health and well-being into considerations of natural resources management;

For

the first time, a tool is available for decision-makers committed to aligning

community culture with project outcomes. For the increasing number of practitioners who believe community and

ecological health to be inextricably tied, the maps provide a physically

defined, cultural-based arena within which decisions are made and resources are

allocated to enhance permanence and diversity in the bio-social ecosystem.

The Discovery

Process yields five scales of human geographic boundaries:

1. Neighborhood

Resource Units (NRU)

2. Human Resource

Units (HRU);

3. Social

Resource Units (SRU);

4. Cultural

Resource Units (CRU); and

5. Global

Resource Units (GRU).

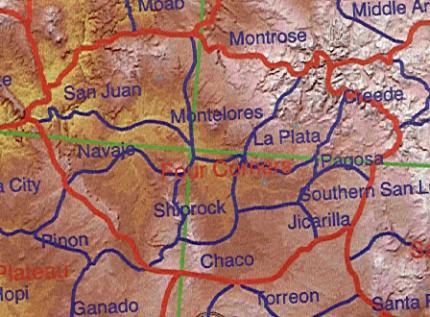

The

figures below show two of these five scales, the Human Resource Unit (HRU) and

the Social Resource Unit (SRU). HRUs are the smaller units and are shown in

blue, while SRUs are larger units and are shown in red. It is best to visualize

blue lines under the red lines, so that SRUs are rightly seen as the

aggregations of the HRUs within them.

Human

Resource Units are roughly equivalent in size to a county but seldom correspond

to county boundaries. HRU boundaries are derived from the seven cultural

descriptors defined below and by self-reporting by residents living in these

areas.

HRUs

are characterized by frequent and customary interaction. They reveal

face-to-face human society where people could be expected to have personal

knowledge of each other and informal caretaking systems are the strongest.

People's

daily activities occur primarily within their HRU including work, school,

shopping, social activities and recreation. Health, education, welfare and other public service activities are

highly organized at this level with a town or community almost always as its

focal point.

A

sense of place; a sense of identity with the land and the people, a sense of a

common understanding of how the resources of their Unit should be managed, and

a common understanding of how things are normally done characterize this

territorial level.

The

regularity of interaction within an HRU reinforces a recognition and

identification by the residents of natural and man-made features as

"home." Because of this

familiarity, boundaries between Human Resource Units are clearly defined in the

minds of those living within them. Human Resource Units aggregate to form Social Resource Units in the JKA

mapping system (Figure Two) (Quinkert et.al. 1986).

Social

Resource Units are the aggregation of HRUs on the basis of geographic features

of the landscape, often a river basin, for example, and on the basis of shared

history, lifestyle, livelihood, and outlook. At this level, face-to-face

knowledge is much reduced. Rather, social ties are created by action around

issues that transcend the smaller HRUs and by invoking common values ("We are

ranching country around here.").

SRUs are best

characterized by a sense of belonging. These are rather large areas and one's intensity of perception as to the

Unit's boundary is much more general than at the Human Resource Unit

level. Those hold a general feeling of

"oneness" who are a part of this regional Unit, and a general understanding and

agreement on values and the attributes of being a part of the Unit.

The physical

and biological environments play a large role in the development of the

cultural pattern at this level of the progression. To a large degree, these environments determine the kinds of

basic industries available for people to develop their culture around, and how

the industries function in the most effective manner to preserve and strengthen

the cultural pattern of the Unit.

Population

density is also a factor that defines and delineates Social Resource

Units. Large areas of high population

density separate Social Resource Units from surrounding areas of lesser

population, but they still reflect in their cultural pattern the broad physical

and biological environment within which they occur.

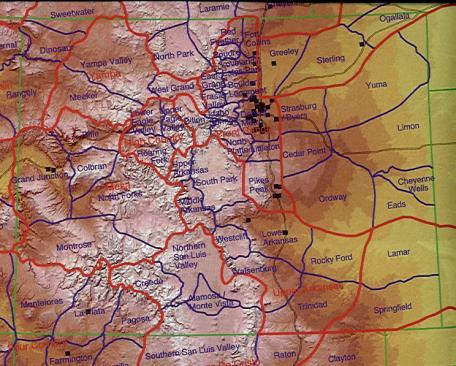

Figure Two

Human Resource Units in the

Four Corners SRU of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona

|

Social Resource Units of Colorado

Social

Resource Units (Figure Three) are usually larger than single cities (the Front

Range SRU, for example, is larger than the metropolitan area of Denver), but

are smaller than most states. However,

a Social Resource Unit will sometimes include portions of several states as is

the case with the Four Corners SRU which includes portions of Colorado, New

Mexico, Arizona and Utah. The

megalopolis of New York City, which includes portions of New Jersey and

Massachusetts, is another example of how Social Resource Units are not confined

by administrative or legal boundaries. Social Resource Units aggregate to Cultural Resource Units in the JKA

mapping system.

Seven

Cultural Descriptors Used in The Discovery Process and to Determine Human

Resource Unit (HRU) Boundaries

ONE: Describe the publics and their

interests

A public is any

segment of the population that can be grouped together because of some

recognized demographic feature or common set of interests. A public may exist currently or at some

future date; it may reside permanently in a geographic area, or may live

elsewhere and have an interest in the management of natural resources. Sample publics include ranchers, loggers,

tourists, small businesses, industries, miners, senior citizens, minorities,

homemakers, youth, preservationists and governmental bodies.

By

identifying publics and characterizing each public's interests, a resource

manager can understand how segments of a population will be affected

differently by resource decision making. Also, predictions can be made about how changing public interests will

influence management in the future.

What publics are within the immediate sphere of influence of

resource management and decision making activities? What are the ongoing interests of each identified public? Which of the publics have specific

resource-related interests? Are there

any public interests or activities that affect resource management activities?

Is there any public that is directly affected by the

resource decision making process? Which

publics currently benefit from jobs generated by the resource outputs? Are there any individuals, businesses or

industries that are dependent upon a specific output?

Which publics could potentially benefit from resource use

and development activities? Which

publics could potentially be affected from a change in current management

activities?

What publics are outside the immediate sphere of influence

of resource management activities, but use the resource or are involved in the

decisionmaking process? Do these

publics have a relationship to the resource because they affect or are affected

by resource management activities?

TWO: Describe the networks

A network is comprised of individuals

who support each other in predictable ways and have a shared commitment to some

common purpose (Figure Four). Networks

may be informal arrangements of people tied together for cultural, survival, or

caretaking reasons. Networks may also

be formal arrangements of people who belong to an organization, club or

association, which has a specific charter or organizational goals. Networks may function in a local geographic

area or may influence resource management activities from regional or national

levels. Examples of informal networks

include ranchers who assist each other in times of need, miners who work on the

same shift, grass-roots environmentalists, or families who recreate

together. Examples of formal

organizations include a cattlemen's association, coal mining union,

preservationist or snowmobile club.

A knowledge of networks citizens form

to express their interests is essential for identifying public issues relating

to management activities and for monitoring the effectiveness of resource

decisionmaking.

What informal networks do each of the identified publics

form to express their interests? What

is the function of each network? When

and where does each informal network gather to share information or services? How do the members of each network

communicate with each other?

Which networks function in an ongoing manner for cultural,

caretaking or survival reasons? Which

networks are temporarily involved around particular events or issues?

What is the informal leadership in each network or who is

respected and why? Are any networks

more effective than others in addressing the issues that concern them?

Which networks extend beyond the local level and function on

a regional or national scale? Are there

any regional or national networks that influence resource management

activities?

What formal organizations, associations or clubs do the

identified publics form to express their interests? What is the purpose of each group? When and where does each formal organization meet to share information

or provide services? How do the members

of each group communicate with each other? Which organizations operate in an ongoing manner and which operate

temporarily?

What is the formal and informal leadership in each

organization or who is respected and why? Are any groups more effective than others in addressing the issues that

concern them?

Which organizations have a membership that extends beyond

the local level and operates on a regional or national level? Are there any regional or national

organizations that influence resource management activities?

Networks are contacted through program

and action development to:

Monitor changing public attitudes and activities

Identify and evaluate public issues

Dispel rumors about management activities

Inform public of current and future plans

Discuss opportunities available to address issues

Prepare for formal public participation and news releases

THREE: Describe the settlement pattern

A settlement pattern is any

distinguishable distribution of a population in a geographic area, including

the historical cycles of settlement in an area. This cultural descriptor identifies where a population is located

and the type of settlement categorized by its centralized/dispersed,

permanent/temporary, and year-round/seasonal characteristics. It also describes the major historical

growth/non-growth cycles and the reasons for each successive wave of

settlement.

Knowledge of settlement patterns

provides a resource manager with a basis for predicting the significance of

probable population changes associated with resource management and development

activities.

Where do people live and how is the population distributed

in the immediate geographic area? Are

the settlement areas dispersed throughout the countryside and/or centralized in

towns and cities?

What is the history of settlement? What types of people came with each successive wave of

settlement? Why did people settle in

the area? Are there any particular

characteristics of the settlement pattern that make it unique?

Have there been any significant increases or decreases in

population in the past? What caused

these? Is the current settlement stable

or on the increase or decrease? What is

causing this trend?

What major changes have occurred during past settlement

cycles? How rapidly have these changes

occurred? How have people handled or

accepted change in the past? Are these

changes easily recalled by people?

What new publics have settled in the area in recent

years? How have long-term residents

accepted newcomers? Is the area settled

with diverse or homogenous publics? Which settlement areas are integrated with diverse publics and which are

not and why?

What future publics can you anticipate residing in the

immediate geographic area? What will be

the possible causes of the future settlement patterns? How rapidly will the settlement occur?

FOUR: Describe the work routines

A work routine is a predictable way in

which people earn a living, including where and how. The types of employment, the skills needed, the wage levels and

the natural resources required in the process are used to generate a profile of

an area's work routines. The

opportunities for advancement, the business ownership patterns, and the

stability of employment activities are also elements of the work routine

descriptor.

A knowledge of work routines can be

used to evaluate how alternative uses of natural resources will affect the ways

people earn a living and how changes in work routines, in turn, will impact

future natural resource uses.

What are the ways in which the people in the immediate

geographic area earn a living? Are

people self-employed or employed by small business or large corporations? What are the primary employment activities

and the approximate percentage of people involved in each sector?

What kinds of skills are required of people in the various

types of employment? What level of pay

is received? Has there been any significant

shift in employment activities or income levels in recent years? If so, has the shift influenced resource use

or management activities?

Are the majority of businesses owned locally or by

corporations and people from outside the area? Are generational cycles of families in the same employment typical?

Are there any work routines that are seasonal in

nature? Are the seasonal jobs taken by

residents of the area or from outside the area? Do many people work two jobs or is it common for families to have

two wage earners? Is the unemployment

significant? If so, among which

publics?

What is the average age of the labor force? Are youth able to find employment in the

area? Are there adequate opportunities

for advancement? Do people change jobs

frequently or work in the same activities most of their lives? Which publics have a strong cultural

identity associated with their work?

Is there a compatible mix of employment activities? Which activities are aggravating each

other? How do current resource

management practices maintain the mix of activities? How could future changes in resource management stabilize or enhance the current employment mix?

FIVE: Describe the supporting

services

A supporting service is any arrangement

people use for taking care of each other. Support services occur in an area in both formal and informal ways. Examples of formal support services include

the areas of health, education, law enforcement, fire protection,

transportation, environment and energy. Examples of informal support activities include the ways people manage

on a day-to-day basis using family, neighborhood, friendship or any other

support system.

A resource manager can use the

supporting services descriptor to evaluate how alternative uses of resources

will affect the ways people take care of each other and how changes in

supporting services, in turn, will impact future natural resource management.

Where are the formal support services such as the

commercial, health, education, transportation, protective, energy facilities

located? What is the geographic area

that is serviced? Which services are

used routinely by people in the area? Which services do people have to leave the area to obtain?

How are the services operated? Are the facilities and services provided adequate for the

area? Which are inadequate and for what

reasons?

What informal supporting activities occur in the area? How do people care for each other on a

day-to-day basis and in times of crisis? Do families, friends, church or volunteer organizations provide support?

How much do people take care of each other on an informal

basis and how much do people rely on formal services? Do people still trade for services or almost always pay cash for

services?

How are the elderly, single parents, youth, poor and others

taken care of? Are informal systems

used such as neighborhoods, or are formal organizations used for

assistance? To what degree do people

take care of their own problems or rely on government agencies and formal

services? Do all people have access to

the supporting services and activities?

Has the amount or type of supporting services changed in

recent years? How has the provision of support

services and activities changed? What

has contributed to these changes?

SIX: Describe the recreational activities

A recreational activity is a

predictable way in which people spend their leisure time. Recreational opportunities available,

seasonality of activities, technologies involved, and money and time required

are aspects of the recreational descriptor. The frequency of local/non-local uses of recreational resources, the

preferences of local/non-local users, and the location of the activities are

also included.

A manager can use this cultural

descriptor to evaluate how alternative uses of resources will affect the ways

people recreate and how changes in recreational activity, in turn, will impact

future resource management.

What are the principal types of recreational activities of

people in the area? Which activities,

sites or facilities are most preferred? Are certain activities seasonal?

What is the orientation of the leisure time activities? Are the activities of individual, family,

team, church or school related? Are

there significant recreational activities in which a wide range of individuals

participate? How do groups like youth

and senior citizens recreate?

How much time is spent in recreational activities? How much money is spent on recreational

activities? What kinds of recreational

vehicles or equipment are used? Do the

majority of activities occur on public or private lands and facilities?

Are there recreational opportunities in the area that

attract people on a regional or national scale? What activities, sites or facilities are most preferred? Are certain activities seasonal? Is there a significant number of businesses

that rely on the income from these recreational activities? Which activities relate to natural resource

uses and management?

Have there been any major changes in recreational activities

in recent years? What events caused the

change? What types of sporting goods or

recreational license sales have been on the increase? What recreational sites or facilities have experienced an

increase of decrease in use and why? Do

current recreational sites and facilities accommodate the demands? What changes in recreational activities are

anticipated in the future and why?

What written and unwritten rules do people use when

recreating? Is there much of a

difference between the recreational activities of residents in the area and

those who temporarily visit the area? How does the type of recreation differ?

SEVEN: Describe the geographic

boundaries

A geographic boundary is any unique

physical feature with which people of an area identify. Physical features separate the activities of

a population from those in other geographic areas such as a valley that people

identify as being "theirs" or a river that divides two towns. Examples of geographic boundaries include

topographic and climatic features, distances, or any unique characteristic that

distinguishes one area from another. Geographic boundaries may be relatively permanent or short-lived; over

time, boundaries may dissolve as new settlement patterns develop and as work

routines and physical access to an area change.

By knowing the geographic boundaries of

a population, a manager can identify and manage the effects of natural resource

use and development that are unique to a particular geographic area.

How do people relate to their surrounding environment? What geographic area do people consider to

be a part of their home turf? Within

what general boundaries do most of the daily activities of the area occur? How far do the networks people use in their

routine activities extend throughout the area?

What is the area people identify with as being

"theirs?" Are there any particular

characteristics, social or physical that people think are unique to the

area? What features attracted people to

the area or provide a reason to stay?

Are there any physical barriers that separate the activities

of a population from those in other geographic areas? Are there any evident social barriers?

What are the predominant uses of the land and what

topographic or climatic features support such activities? What percentage of the geographic area is in

the private and public sector? Is most

of the private land owned by year-round residents or by people from outside the

area?

Have

there been any significant changes in the use of the land and its resources in

recent years? What has caused the

changes? How have these short- or

long-term changes affected people and their ways of life? How accessible is the area to external

influences? What kind of

influences? Are these beneficial or

negative impacts on the area?

Human

Geographic Issue Management is the process of creating productive harmony at

the project level by assisting change agents in integrating resource

decision-making with considerations of community health. Issue management is

the ability of an organization to identify and respond to public issues in a

timely and appropriate fashion in order to culturally align land management

agencies with the informal community systems which they serve. It is a way to

achieve bio-social ecosystem management because it allows a balance to be

created between biophysical and human habitats.

The theory of

issue management is that issues, or citizen statements which can be acted upon,

present the greatest range for responsive options if issues are identified in

the emerging stage of development. Issues that are allowed to become

disruptive, by definition, are resolved at higher levels of formal society. To

identify emerging issues, it is necessary to have direct contact at the

informal level of community. It is at this level where people are just

beginning to become concerned about real or perceived changes in their

environment and to mobilize their networks for action. Issues that are resolved

at the emerging stage increase community resilience that in turn provides local

support for agency projects. Moreover, issues resolved at this stage cannot be

appropriated at regional and national levels for political purposes. Figure

Four displays the issue management process.

The issue

management process provides social, cultural and economic information through

face-to-face interaction that is essential for day-to-day operations, baseline

community studies, environmental documents, as well as for planning and

analysis. It is a means to develop relationships that foster community

partnering and collaborative issue resolution. The JKA Group has been

successful in applying these concepts at all levels and scales of agency and

community operations.

Figure Four

Issue Management at

the Project Level

(Source:

Preister and Kent 1997)

Practitioners

of Issue Management:

1. Describe

communities in social, economic, and cultural terms.

2. Identify and

map informal networks and major communication pathways.

3. Identify the

issues related to the community and to land management in a systematic way and

incorporate them into agency decision-making.

4. Institute

"issue-tracking" mechanisms within the agency in order to enhance

responsiveness and stable decision-making.

Geographic

Information Systems (GIS) provide the technical capability of applying this

kind of responsiveness to regional, multi-disciplinary and multi-jurisdictional

efforts currently underway, such as:

The Mojave Desert Ecosystem Program,

Watershed coordination efforts in the Central Valley of

California,

The Southwest Strategy in Arizona and New Mexico to

coordinate collaborative ecosystem recovery.

These

and other efforts are characterized by increasing sophistication in the

collection and display of biological data and in the monitoring of such data

for planning and management purposes. However, the sophistication on the social

and cultural side has been very low. At best, census data and other social and

economic information are displayed with no context of process within which to

use and provide value to the information. Nowhere are displayed citizen issues,

trends affecting local communities, key communication pathways, or the beliefs,

traditions, values, aspirations and visions of local communities.

The

danger of this limitation is that ecosystem decisions are driven too much by

biological and physical science, technical considerations and agency interests.

Science, of course, is valued and necessary but when its application is not

tempered by the context of human considerations, the "tyranny of the expert"

syndrome can dominate, with disastrous biological, political, cultural and

economic costs.

The

concept of Social Resource Unit (SRU) was first used in relation to work with

the U.S. Forest Service Region 2 and is described in Kent and Greiwe (1978).

Our regional efforts stem from work we did with the City and County of Honolulu

in the late 1970s in which we geographically mapped the island of O'ahu into

human resource units. The island of O'ahu had a population of about 800,000.

Community fieldwork identified informal networks, emerging issues, key

caretakers, communicators, and opportunities, for use by the city in dealing

with intense development pressures (Kent and Ryan 1980, 1981). This work

pre-dates GIS capability.

In

1991, we assisted Washoe County, Nevada with the implementation of their Issue

Management program in which county staff performed similar human geographic

mapping. The result was a map showing neighborhood boundaries identified by

residents and a system for monitoring emerging, existing and disruptive issues.

Their system has the ability to call up issues either by geographic location or

by type of issue. The system also allows for the tracking of issues and their

resolution over time. Staff print "Issue Alerts" for their county commissioners

so that action can be taken in a timely manner and costly disruptive issues

prevented from occurring (Kent 1993). The Washoe County system has not yet

integrated the data files of description and issues with the GIS mapping.

Our

vision for a GIS-based Human Geographic Issue Management System presumes that

baseline social, economic and cultural data have been gathered, and human

geographic boundaries displayed through maps are generated. Data sets capable

of being displayed spatially that we feel are important in promoting a

bio-social ecosystem approach include:

Cultural description (settlement patterns, publics,

networks, work routines, support services, recreation activities, geographic

features);

The range of public issues related to community life and to

resource management;

Social and economic trends reported by residents (often

pre-dating statisticians by as much as five years) that present pro-active

opportunities;

Communication pathways (gathering places, informal networks,

the who, where, and when of communicating);

Identification of essential and effective civic protocols

citizens use to manage their relationships with each other and the land;

Opportunities identified by citizens for resolving current

community and resource management challenges.

When this information is paired and

layered with biological and physical data, a powerful tool has been created for

anticipating the effects of decisions and for fostering collaboration in

considering possible courses of action.

Issue

management focuses clearly on the use of federal lands to address the social

benefits, issues and impacts created by use of the federal resource. Hence,

poverty, underemployment, growth rates, sector changes (agricultural,

industrial, services), affordable housing, transportation, recreation, and

urbanization are related to community health. These factors are the concerns of

federal land use management agencies to the extent that they impact public

lands and to the extent that federal decisions, within the bounds of

sustainable ecosystems, can contribute to addressing them. Indeed, we are

entering an era where urban policy in the western United States is imperative

for land use agencies if resource quality and availability is to be assured in

the future.

Earlier

in this paper we have made the case that NEPA's Section 101 permits and

encourages, through its productive harmony clause, the scrutiny of and response

to social and cultural considerations. It is the authors' experience that ample

legal justification exists in Section 101 for agencies to consider "off site"

impacts, including those listed above. At M~kua Beach, Hawaii, working through

the Department of Defense, off-site considerations permitted by NEPA and

Environmental Justice guidelines sustained the military use of the beach for

training purposes and accomplished several social objectives as well (James

Kent Associates and Institute for Sustainable Development 1998a, 1998b).

A

broader perspective, such as we are suggesting, has resulted in successful

resolution of community concerns regarding federal actions and the creation of

productive harmony at the local level. For the first time, managers can determine how far "off-site" they have

to go with various issues - either to the line of the Human Resource Unit or to

the line of the Social Resource Unit. In addition, the maps provide a

geographic context for "staffing projects through the culture" rather than

imposing projects "on the culture."

Caldwell, Lynton K.

(1998) Beyond

NEPA: Future Significance of the National Environmental Policy Act. The

Harvard Environmental Law Review 22(1): 203-239.

Council on

Environmental Quality

(1996) The

National Environmental Policy Act: A Study of Its Effectiveness After

Twenty-five Years. CEQ, Executive Office of the President, November.

James Kent

Associates

(1993) Issue Management Handbook, Washoe County

Issue Management System, Washoe County Department of Comprehensive Planning,

Reno, Nevada; June.

James Kent Associates & Institute

for Sustainable Development

(1998a) APPENDIX

G: Decision Support Document: Community Resources Summary and Recommendations,

Marine Corps Amphibious Training at M~kua Beach. Prepared for Commanding

General, Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Environmental

Assessment for Marine Corps Amphibious Training in Hawaii, June.

James Kent Associates & Institute

for Sustainable Development

(1998b) Guidelines

for Community Interaction: Developed as Part of an Expanded Culture Assessment,

Environmental Assessment Project for the Marine Corps Amphibious Training in

Hawaii, July.

Kent James A. & John Ryan

(1980) Documentation

of the Methodology Used in Developing Guidelines for a Social Impact Management

System for City and County of Honolulu. Honolulu, HI: Honolulu Department of

General Planning, March.

(1981) A

Social Impact Management System for Honolulu: Final Phase Two Report. Honolulu,

HI: FUND Pacific Associates, July.

Kent, James A.

& Richard J. Greiwe

(1978) The Social Resource Unit: How Everyone Can

Benefit from Physical Resource Development. Mining Year Book, National Western

Mining Conference and Exhibition, The Colorado Mining Association.

Preister,

Kevin and James A. Kent

(1997) Social

Ecology: A New Pathway to Watershed Restoration. IN Watershed Restoration:

Principles and Practices, by Jack E. Williams, Christopher A. Wood and

Michael P. Dombeck (eds.), Bethesda, MD.: American Fisheries Society.

Quinkert,

Anthony K., James A. Kent & Donald C. Taylor

(1986) The

Technical Basis for Delineation of Human Geographic Units. Denver, Colorado:

SRM Corporation for U.S. Department of Agriculture, April.

Appendix A

Appendix A |

Table of Contents | Appendix C

|

| Natural Borders Homepage |